Trace

Project Intro

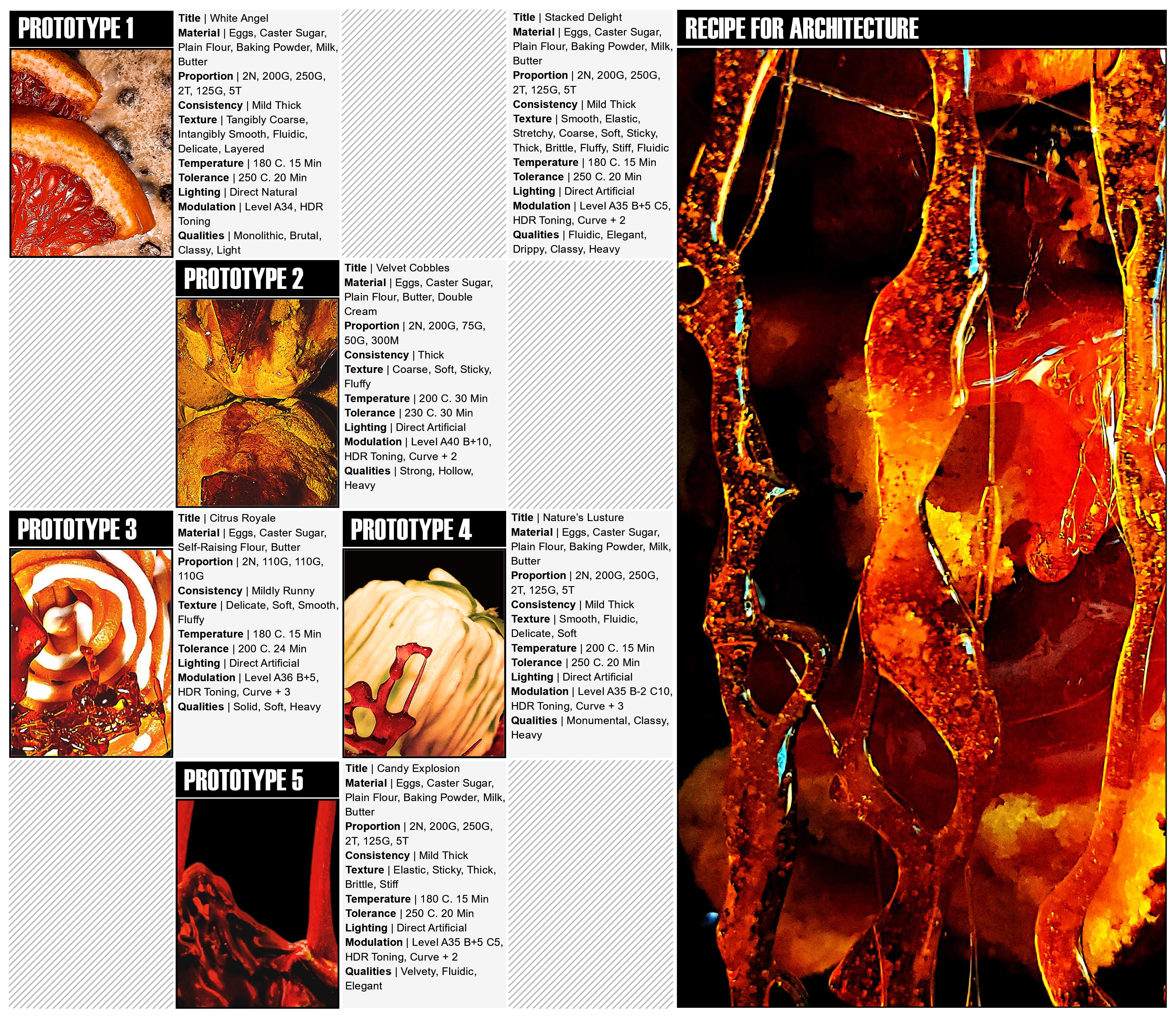

The theme, "Confectionery: The Art of Making Confections," uses Metamorphosis as the conceptual foundation for individual projects. The design process begins by drawing a parallel between architecture and the culinary arts, much like how a chef approaches cooking, where recipes are treated as algorithms. This approach is deliberately non-mechanistic, focusing on the thoughtful selection and preparation of components. Just as ingredients can be combined in various ways to create unique culinary experiences, the same principle is applied to architectural composition.

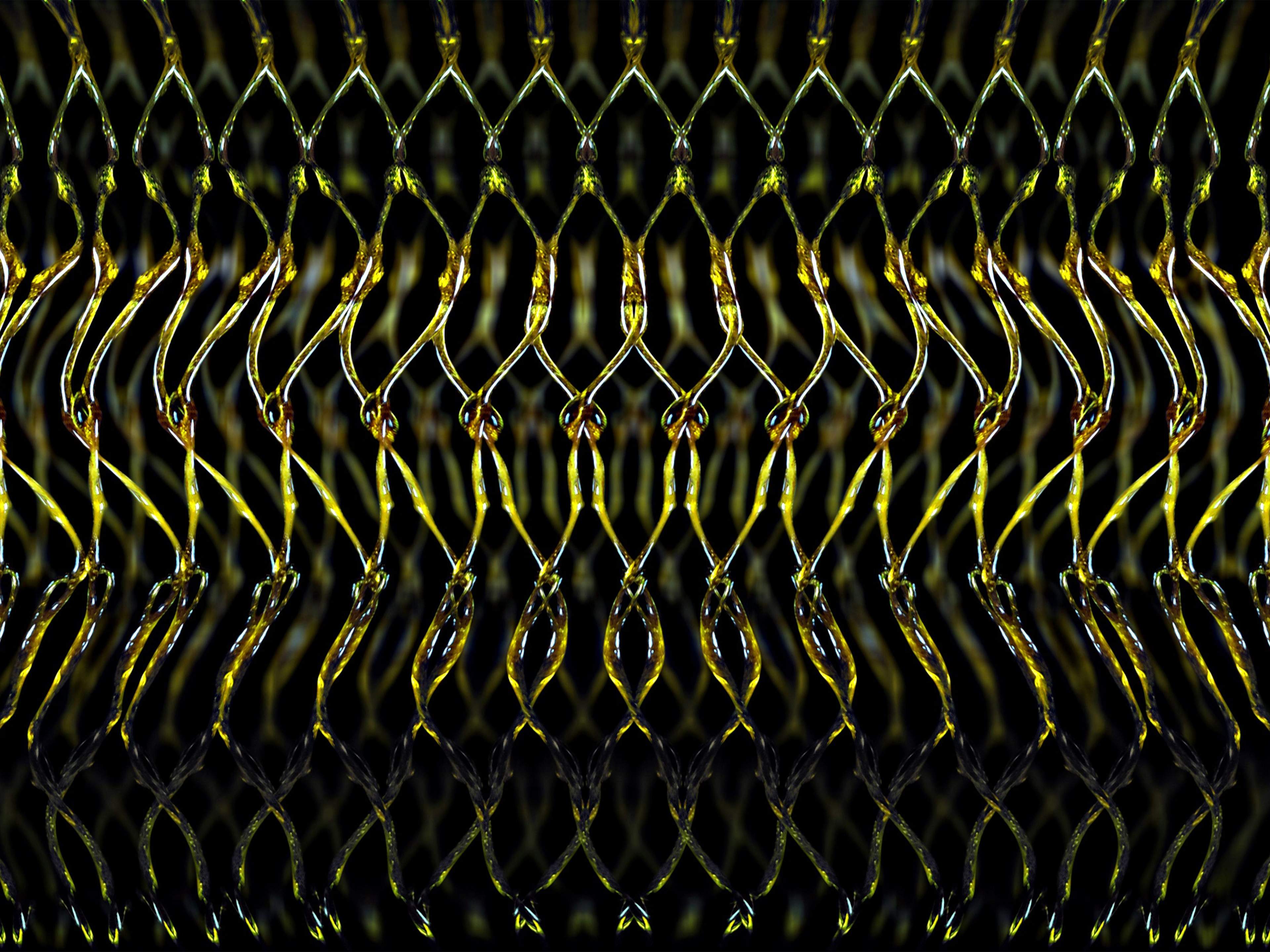

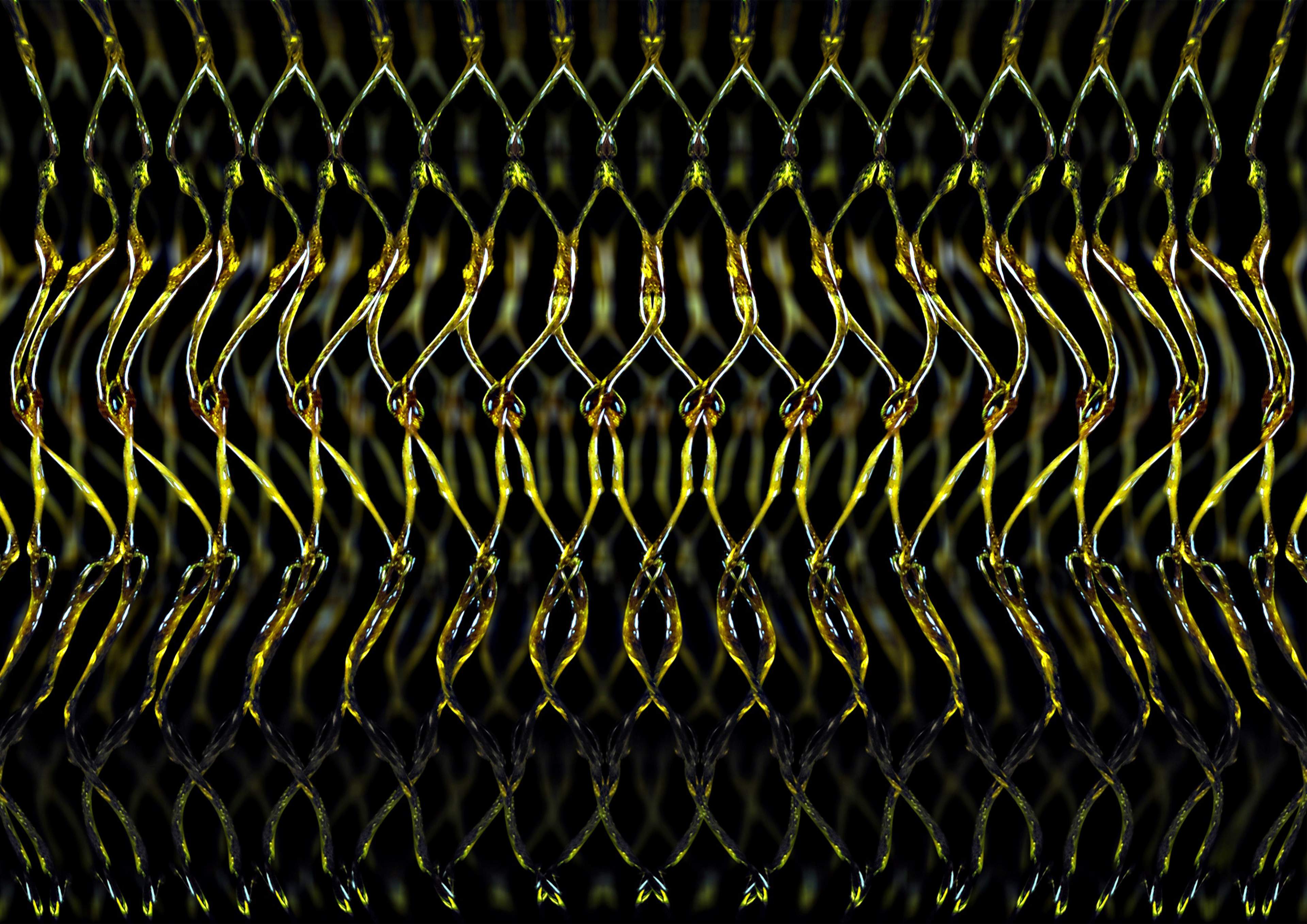

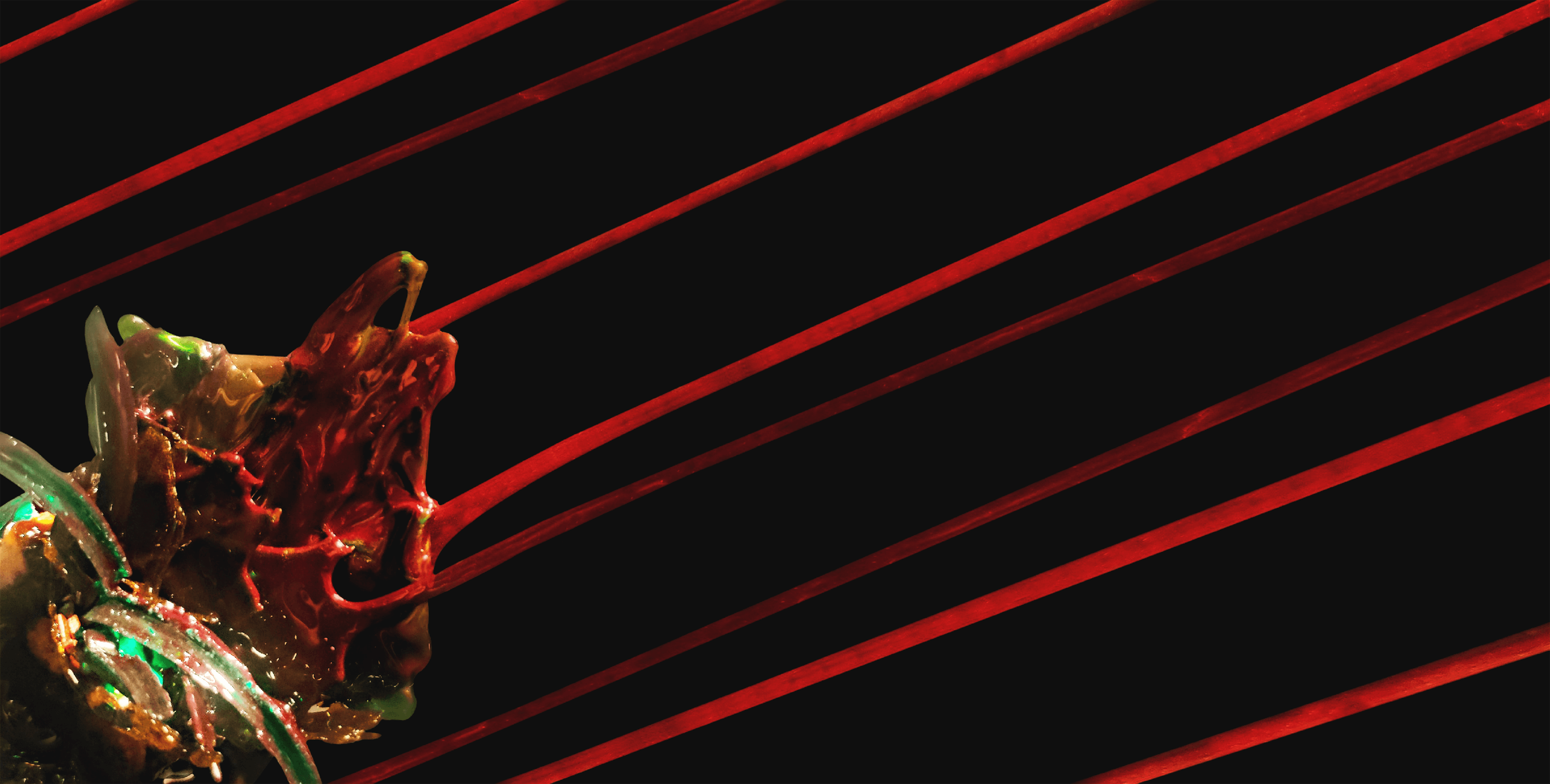

In this context, architectural elements are envisioned to be both visually appealing and sensually engaging, stimulating not only the eye but also evoking a sense of taste. The project evolves through the conceptualization of confections, captured in a series of photographs that explore diverse textures and surfaces. This study aims to analyze and understand the inherent tendencies of different materials, ultimately leading to the development of a unique architectural recipe.

2020

Year

Published

Status of the project

Project Details

Site Location | Architect's Kitchen |

Project Type | Prototyping & Experimentation |

Time | 2020.09 – 2020.12 |

Status | Recipe Book Published |

Tools used | Baking, Photography, Adobe Photoshop |

Supervisor | Mr. Joel Chappell and Mr. Andrew Holmes |

Ideology

In 8 AD, the Roman poet Ovid eloquently captured the inherent mutability of nature, famously contemplating the unimaginable transformation of an eagle emerging from an egg. His poetic narrative transcended the ordinary—rocks metamorphosed into humans, and over 250 myths unfolded as a rich source of inspiration for artists ranging from Shakespeare to Bernini. Ovid articulated these fantastical changes through language, while the sculptor, with extraordinary manual skill, etched these transitions into marble. This act required not only imagination but also the capacity to translate mental visions onto paper through the discipline of drawing.

In our contemporary era, digital technology has radically transformed this creative process, liberating the transfer of three-dimensional images from the constraints of analog methods. This shift has redefined our understanding of materials. With the advent of 3D printing, imagined forms can now be materialized tangibly, bridging the gap between concept and physical reality.

For designers operating within this evolving landscape, the central question becomes: how can such transformations be achieved today? This inquiry demands a critical re-evaluation of materials—not only their intrinsic properties but also our assumptions about how they should be used, assembled, or whether such constraints should even exist. The Modernist ethos of "truth to materials" may, in fact, hinder imaginative possibilities. By contrast, like a chef in the culinary arts, the designer can break free from inherited dogmas, driven instead by new criteria of innovation, redefining the boundaries of materiality and form.

Process

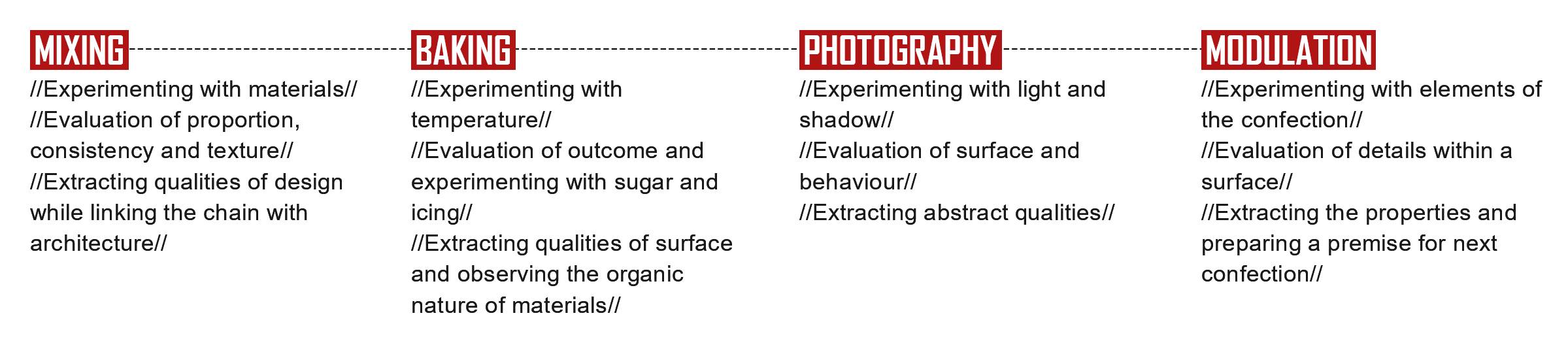

Drawing parallels to the systematic methodology of a pastry chef, the contemplation of architecture follows a similarly structured approach. Over the course of fourteen weeks, a cyclical process unfolds—each week’s learning builds upon the last, informing the creation of distinct architectural “recipes.” The overarching goal is to distill these cumulative insights into a refined architectural formulation by the fourteenth week, encapsulating a comprehensive synthesis of the evolving design principles and conceptual explorations.

Inference

The inception of awareness in a newborn manifests in its ability to look, perceive, and recognize long before the acquisition of language—embodying the truth that "seeing comes before words." This primal act of seeing anchors our presence in the world; we interpret and articulate our understanding of it through language. Yet, the relationship between what we see and what we know is never fixed—it remains in constant flux.

Renowned Surrealist painter René Magritte, in his work The Key of Dreams, suggested that our perception is profoundly shaped by our knowledge and beliefs. Consider the Middle Ages, when the belief in the physical existence of Hell gave the sight of fire a meaning entirely different from today. Their concept of Hell was not abstract—it was vividly informed by the visible: the consuming flames, the lingering ashes, the searing pain of burns.

Love, too, exemplifies a form of seeing that transcends language—a preverbal, embodied perception that finds its fullest expression in the intimacy of physical connection. This mode of seeing is not merely a passive response to external stimuli—it is an act of intention. To look is to choose. We bring things into our field of awareness by actively deciding to see them. Vision, then, is a continual, dynamic process—shaping and situating everything in relation to ourselves.

Yet, vision is not a solitary act. To see is also to be seen. We come to recognize our presence in the visible world through the gaze of the other. This mutual exchange of sight affirms our belonging, embedding us within a shared reality.

An image is a reconstruction or reproduction of sight—a set of appearances detached from its original time and place, preserved for contemplation. It suspends the fleeting nature of perception, freezing a moment for interpretation across time.

Each image carries a particular way of seeing—a unique perspective. Unlike texts or artifacts, images bear witness to the worlds people inhabited in past eras with remarkable immediacy. In this sense, they offer a kind of clarity and richness that literature often cannot. This doesn't diminish the imaginative or expressive power of art; rather, it underscores that the more imaginative the image, the more deeply it invites us to share in the artist’s way of seeing.

However, when an image is framed as a work of art, it is inevitably filtered through learned assumptions—about Beauty, Truth, Genius, Civilization, Form, Status, Taste, and more. These inherited frameworks shape how we interpret what we see.

Yet many of these assumptions have become outdated, misaligned with contemporary realities. To truly engage with the world-as-it-is, we must look beyond mere objective facts. We must embrace the subjective, the conscious, the experiential. As John Berger eloquently argues in Ways of Seeing, perception is never neutral. It is charged with meaning—historical, cultural, and personal.